“Then you see kids, good kids from good families. Back home, these kids would help little old ladies across the street. They would also go to Bible study. Yet, they do these horrible things. They’re in the country for a little bit, and it’s like the veneer of civilization peels right off of them.”

The quote above is from a Vietnam Veteran. He was interviewed for the 10-part documentary The Vietnam War by Ken Burns. He was talking about “acts of war”. In particular, the acts of savagery committed by some American soldiers while serving in Vietnam.

At an average of 90 minutes per episode, completing the series was challenging. But I did, and I have a lot of takeaways. There are hours of battle footage, commentary, and interviews. All the players are involved, including politicians and soldiers from South and North Vietnam, and the enemy. It covers all of the geopolitics involved in Cold War Southeast Asia. Per usual, Burns provides an honest, balanced and unflinching look at one of the darkest chapters in recent history.

The veterans interviewed did the unusual. They talked openly about their experience. They ranged from the reluctant draftee to the hardened veteran. There was also the wide-eyed, eager recruit seeking the honor and glory his father achieved. Finally, there was the everyday guy from Anytown, USA, who felt the call of Patriotism. They all went to the same place, but all came back very different. It wasn’t like the last war, their Dad’s war. And glory was not in the cards.

A lot of men did and saw things that would haunt them. When villages were razed, livestock slaughtered, suspected enemies gunned down, and food supplies destroyed, part of following orders, a lot of soldiers found their moral compass in danger. Some made “deals with the devil” to rationalize their acts. One soldier said, “I will never kill another human, but there’s no limit to how many Vietcong I will waste.” If they are no longer people, then it becomes easier. They are the enemy; they do not matter.

Then some stretched the thin red line even further. Rapes, mass killings of civilians, and excess brutality sometimes occurred. As it says above, it was as if the veneer of civilization had worn off of them.”

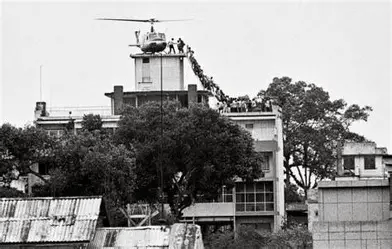

At home, the war had changed people as well. The escalating campaign was enormously controversial. Young people broke ranks with their parents’ beliefs. Students took to the streets and challenged authority figures. Peaceful protest morphed into violence as frustration with a growing conflict grew. Pictures of bombing campaigns and burned children were finding their way into American living rooms, and people were outraged. Some activists decided that violence was justified, and riots and bombings occurred. It culminated when the National Guard opened fire on a crowd at Kent State and killed four. One veteran lamented, “It has gotten so bad we are killing our own at home”. Even after the Saigon airlift of ’73, this country was divided and forever damaged.

When the soldiers returned, there was no ticker tape parade. The hostility towards the war had been directed towards those who had been charged with fighting it. The brave men and women who fought the unpopular war returned from planes and boats. They were unjustly called “baby killers” and were spit upon. These people are still owed the Welcome Home they deserved. But as I have said. Everyone and everything had changed.

What are the rules of civilization? Are they inherent? Are we born to act rationally and be decent to each other? Is it the job of parents to instill the concept of society in us? Is the veneer of civilization so thin that it can be easily worn down? Can we easily descend into barbarism and savagery?

You may not know what it was like to see the political climate of the late 60’s and early 70’s. It isn’t too late. You can still see it. Just turn on your TV. Because it’s still happening, only the target of the outrage is different. Riots, Nazi flags, death threats, mass shootings, shouting, fighting, people just being ugly to each other. So I have to ask; if the veneer of civilization is but a thin covering, what’s underneath?